Open Sesame

Curated by Ola El-Khalidi

apexart, Manhattan

17 January -- 2 March 2013

Through a small collection of objects, maps, letters, and photographs, Open Sesame leads viewers back in time to 2 August 1990— the morning Iraq invades Kuwait. The exhibit pieces together the miscellaneous belongings of children at the time, whom curator Ola El-Khalidi refers to as the “Open Sesame” generation. “Open Sesame” is also the Arabic name for the pan-Arab edition of the American children’s TV series Sesame Street, on which one of the children was to appear that day, but never did.

Open Sesame captures many similar moments of loss and anxiety that had a profound effect on the generation: the separation of childhood friends, the long and unexpected drive to a safer, though stranger place, and the dispersal of families across various countries and time zones. For these children, Kuwait was a utopia: “…everything was available, life was easy, neighbours cared, and families were close.” Consequently, the invasion marked the end of childhood; it meant transitioning out of “the land of dreams” and into reality. From that point forward, Kuwait existed only in memory, one that El-Khalidi describes as being “drenched in nostalgia, trauma, and utopianism.” Using this premise as a starting point, the exhibit portrays this generation’s life in Kuwait and the experience of the Gulf War as a close examination of childhood, as well as a coming of age event. Based on the exhibit’s brochure, Open Sesame recovers delicate moments of loss from individual members of the generation—which for the longest time have been hidden or silenced—in the aim of sharing, revaluing, and connecting them with the present.

One of the best examples reflecting such unison of remembrance and loss is Makan Collective`s wall-sized "Regional Map," which is part of the larger installation Twenty Two Years Today (2013), the exhibit’s second largest work. The giant map traces the route from the Kuwait-Iraq border all the way to Amman, pointing out the cities of Bagdad, Ramadi, Rutba, and finally, the Tarbil Border Crossing, the last stop before entering Jordan. Placed on different points along the route lie two-dimensional black and white convoys mimicking the mass departure, and fighter jets soaring over Iraq’s northeast. Attached to the map, a Walkman plays Warda and Sabah Fakhri, offering another dimension to the ride, and recreating the atmosphere of a young individual’s migration.

At first glance, the map appears minimalist, with only points and dashes charting the course, and a few names of stopovers; no mentioning of landmarks or distinguishing terrain, only thin black lines that designate the borders between one country and the next. If it were not for these lines, viewers could not tell where one country begins and the other ends. Nonetheless, the map makes use of its white space to imply the vast expanse of the Arabian Desert that extends beyond borders and stands in the way of the refugees, as symbolised by the convoys. Here, the desert appears as both safe haven and threat, where the refugees may find shelter but are at equal risk of getting lost or falling prey to its perils. In the exhibit’s brochure, El-Khalidi mentions the story of a father who was bitten by a sand fly while driving a truck full of his family’s belongings through this very desert. He developed leishmaniasis, and his face was “scarred forever.”

[Makan Collective, installation view of "Twenty Two Years Today" (2013). Image courtesy of apexart.]

[Makan Collective, installation view of "Twenty Two Years Today" (2013). Image courtesy of apexart.]

[Makan Collective, detail of "Twenty Two Years Today" (2013). Image copyright the artists. Courtesy of apexart.]

[Makan Collective, detail of "Twenty Two Years Today" (2013). Image copyright the artists. Courtesy of apexart.]

Also prepared by Makan collective (artists Diala Khasawnih and Samah Hijawi) is a sixteen-page journal entry documenting another individual’s evacuation experience. Written in a blue ballpoint pen on aged, lined paper, each page bears its number at the top right corner. The writing is neat and consistent, articulates physical descriptions, feelings and thoughts, and describes the weather. In one passage, the author mentions a western wind that brings rain and later, snow. Symbolically, it is indeed the west wind that we often associate with change, and more specifically, rebirth. Yet the journal’s emotive power lies in its intimate narration; its words transport us to the desert where we accompany its young author on both the physical trip to Jordan, and the mental journey of leaving home behind. Though the writer must endure several nights of cold and sleeping in cars, the last lines echo the amazing sense of adaptability—even wisdom—often found in children and young adults, “I will not refer to it as a hardship as much as an experience for life is full of events and this is just another one!”

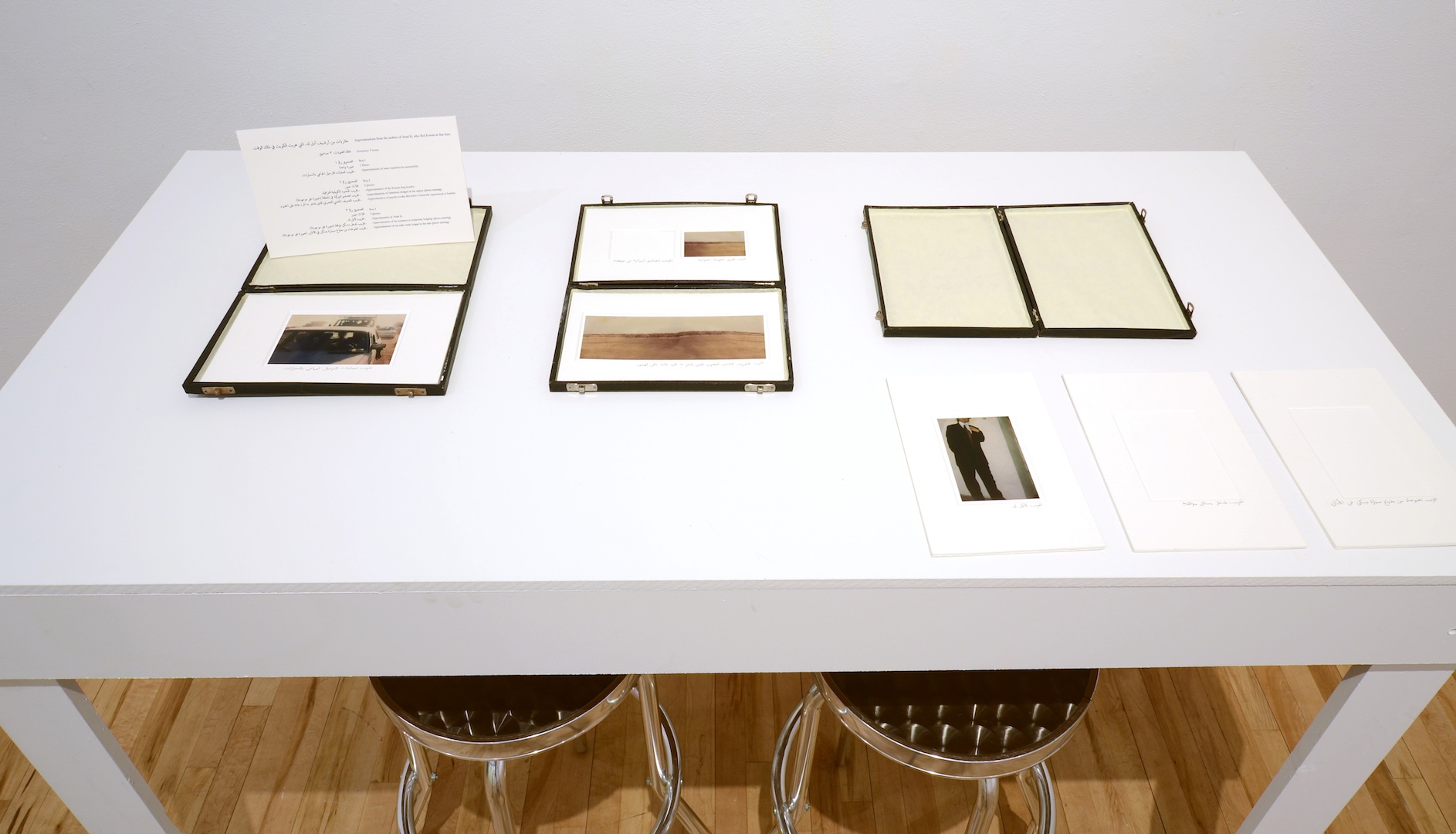

Nearby and encased in glass, rest a series of photographs taken during the desert exodus, entitled, Approximations from the archive of Amal K, who Left Kuwait at that time (2013) by Rheim Alkadhi. Although the photographs have been acquired from the private collection of Amal K., Alkadhi has mounted them on archival rag boards and inscribed them with titles herself. In an "Approximate view of a moment within an expulsion," an eighties-looking car appears in the foreground, presumably full of family members as it makes its way across the desert. Behind it emerges a pickup truck, similarly packed with passengers, with another white car behind it, filled with even more passengers. All of the faces appear blurry; viewers can only distinguish the basic silhouettes of heads and bodies, a simple shape of a steering wheel, and the only part in focus—a man’s left arm dangling out of the driver’s seat window. The grainy texture of the photograph evokes an intense heat; the desert sun shines in the background, and a dusty, unsettling haze materialises all around.

[Rheim Alkadhi, "Approximations from the archive of Amal K, who Left Kuwait at that time" (2013). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of apexart.]

[Rheim Alkadhi, "Approximations from the archive of Amal K, who Left Kuwait at that time" (2013). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of apexart.]

[Rheim Alkadhi, "Approximations of a moment within an expulsion" (2013). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of apexart.]

[Rheim Alkadhi, "Approximations of a moment within an expulsion" (2013). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of apexart.]

Most striking however are the empty frames of missing photographs in Alkadhi’s sequence. While reiterating the exhibit’s main themes, they nevertheless ignite the viewers’ imagination. What happened to those specific moments in time? What did they capture? Does anyone remember? Will we ever know? Certainly these questions relate to El-Khalidi’s central question, “What happened on August 2, 1990?” which prompted her interviews with the Open Sesame generation. Yet Alkadhi’s work does not attempt to present us with answers, but rather, propels us into the realm of uncertainties. The artist allows viewers to enter into an unmediated discussion with the images, and envision other narratives. Unlike Khasawnih and Hijawi’s journal, Alkadhi’s work contains no definitive markers in terms of time, place, or even weather, but creates room for each viewer to construct their own narrative in the allotted space framed within the exhibit.

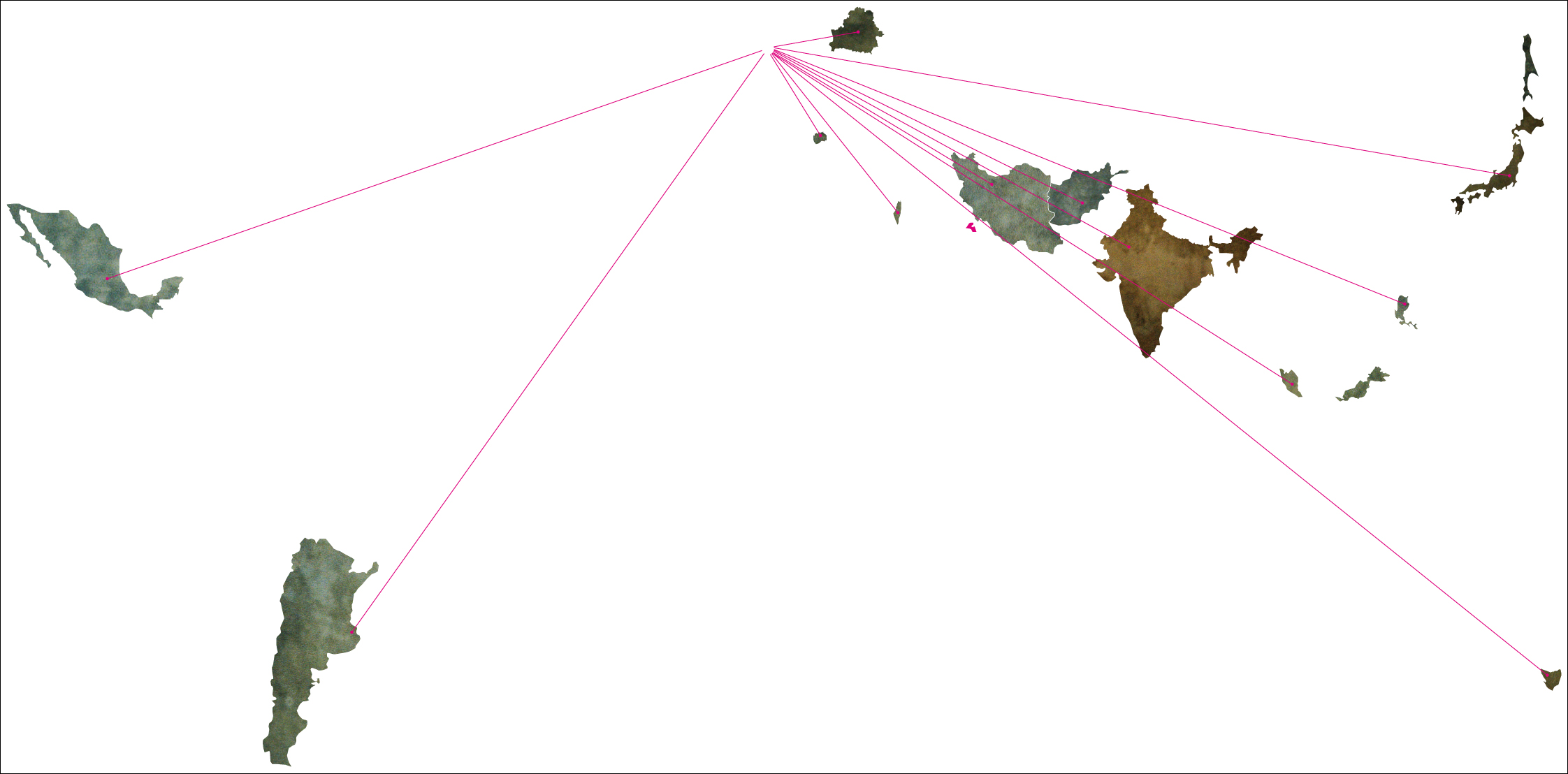

In a flat, graphic representation of the world entitled Source Map, Jeanno Gaussi breaks the seven continents away from their traditional arrangements. Red lines stretch out from every landmass, connecting to an ocean point in the top centre. The map appears out of scale and excludes the boundaries that define each country. The title of the piece leaves us wondering what the map really intends to show, or perhaps, transcend. Do the red lines originate in the places that people came from or fled to? Why is the meeting point not on the mainland of any continent? The absence of boundaries could possibly suggest art’s disinclination to politics. Indeed, the exhibit makes no use of nationality or political affiliation of the individuals involved, regardless of the political situation that the art is based on. Even though the Gulf War was in and of itself political, Open Sesame directs no special attention to political loyalties at the time. Instead, the exhibit emphasises home as a place in time—Kuwait up until the invasion—a home for some outside their country of origin, and one that Gaussi portrays as a meeting point of people from all around the world if momentarily, before they are dispersed once more.

[Jeanno Gaussi, "Source Map" (2013). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of apexart.]

[Jeanno Gaussi, "Source Map" (2013). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of apexart.]

In Table Box, El-Khalidi displays a few of the generation’s mementos that she collected through her research and refers to in the exhibit’s brochure. They include a Nescafe jar filled with sand from Kuwait to Amman in 1990, wedding sheets, a glove, a napkin from the Kuwait Towers, a plastic Salmiya Co-Op bag, and two pieces of cutlery. The display also features reading material, including newspaper cut-outs, a “Majed” comic, an illustrated story, a copy of the popular children’s magazine “Al-Arabi,” a diary, a Christmas card, and a homework jotter signed by a teacher. The items not only serve as artefacts of former lives, but also, each item carries with it its own narrative of life in Kuwait, and an endurance despite war and dislocation. The card for example, was a confession of love from a neighbour to a young boy, given to him right before he fled Kuwait with his family. In the brochure El-Khalidi notes, “…although it was only August, it was the only card [she] could find.”

As curator, El-Khalidi describes the exhibit as a “sincere attempt at documentation,” where the Gulf War is recorded as a turning point in the lives of a generation of youths. Through glimpses of their lives in Kuwait, we feel the trauma of the unexpected event that turns them into refugees overnight, and scatters them across distances in a matter of days. Yet, the exhibit also traces the fragile transition from childhood to adulthood that all members of the generation endured amidst the turmoil of war, separation, and even diaspora. Similarly, Open Sesame highlights the movement from childhood carelessness, ignorance, and naïveté, to a position of experience, maturity, and knowledge. Moreover, it exposes the rift between the generation’s two divergent lifestyles: a utopian childhood in Kuwait disrupted by war, to a young adult life elsewhere as a result of exodus. Calling on its legendary title—"the command to open," Open Sesame unlocks to viewers some of the hidden and silenced memories of the Gulf War, which after twenty-three years, have finally come to light.

![[Detail of \"Table Top\" installation from the exhibition Open Sesame. Courtesy of apexart.]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/opensesame15.JPG)